Advanced Physics-Based Rendering:

PART 1: Implementing Gravity and Particle Systems

As a principal software engineer, I recently led the development of a sophisticated physics-based rendering system using C++ and OpenGL. This project demonstrates the implementation of particle systems under the influence of gravity, utilizing various numerical integration methods. In this article, I’ll dive deep into the technical architecture, implementation details, and key features of our rendering system.

Architecture Overview

Our physics-based rendering system is built on three main pillars:

- A custom math library for 3D vector operations

- A particle system with different integration methods

- An OpenGL-based rendering pipeline

Let’s examine each component in detail.

Custom 3D Math Library

At the core of our system lies a custom 3D math library, implemented in math3d.h. This library provides a vector3f class, which encapsulates operations for 3D vectors:

class vector3f {

private:

float x, y, z;

public:

// Constructors and basic getters/setters

vector3f operator+(vector3f& v) {

return vector3f(x + v.getX(), y + v.getY(), z + v.getZ());

}

vector3f operator-(vector3f& v) {

return vector3f(x - v.getX(), y - v.getY(), z - v.getZ());

}

// Other operators and methods like *, /, length(), makeUnit(), etc.

};

This custom library allows for efficient and intuitive manipulation of 3D vectors, which is crucial for physics simulations and rendering.

Particle System

The particle system is the heart of our physics simulation. It’s implemented in Simulation.h and Simulation.cpp. The system manages a collection of particles and updates their positions and velocities based on physical laws and numerical integration methods.

Key features of our particle system include:

-

Multiple Integration Methods: We’ve implemented three numerical integration methods:

- Euler

- Euler-Cromer

- Verlet

-

World Collision Handling: Particles bounce off the boundaries of the simulation world.

-

Energy Computation: The system calculates kinetic and potential energy of the entire particle system.

Here’s a snippet of the Simulation class structure:

class Simulation {

public:

float timestep;

int noPt; // Number of Particles

vector<Particle> particleList;

float commonMass;

float kinEn;

float potEn;

virtual void simulate() {

clearForces();

applyForces();

solveWorldCollision();

for (int j = 0; j < noPt; j++) {

switch (particleList[j].getIntegration()) {

case Euler:

simulateEuler(&particleList[j]);

break;

case EulerCromer:

simulateEulerCromer(&particleList[j]);

break;

case Verlet:

simulateVerlet(&particleList[j]);

break;

}

}

computeSystemEnergies();

}

// Other methods...

};

OpenGL Rendering Pipeline

The rendering is handled by an OpenGL-based system, implemented in GL_Related.cpp and GL_Related.h. This system sets up the OpenGL context, handles window creation, and manages the rendering loop.

Key features of our rendering system include:

-

Custom Window Management: We’ve implemented a custom window class that wraps the Win32 API for window creation and event handling.

-

OpenGL Context Setup: The system sets up the OpenGL context and handles the initialization of OpenGL functions.

-

Rendering Loop: A main loop that updates the simulation and renders the particles.

Here’s a snippet of the main rendering loop:

void Draw(void) {

glMatrixMode(GL_MODELVIEW);

glLoadIdentity();

gluLookAt(0, 0, 45, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0);

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT | GL_DEPTH_BUFFER_BIT);

drawWalls();

for (int a = 0; a < simb->noPt; a++) {

vector3f pos = simb->particleList[a].getPosition();

vector3f color = simb->particleList[a].getColor();

glTranslatef(pos.getX(), pos.getY(), pos.getZ());

drawCube(color);

glTranslatef(-pos.getX(), -pos.getY(), -pos.getZ());

}

// Display simulation information

glColor3ub(100, 100, 100);

glPrint(-5.0f, -14, 0, "Time elapsed (seconds): %.2f", timeElapsed);

glColor3ub(100, 0, 0);

glPrint(-5.0f, 13, 0, "Simple Gravity System");

glPrint(-5.0f, 12, 0, "System Kinetic Energy: %.2f", simb->kinEn);

glPrint(-5.0f, 11, 0, "System Potential Energy: %.2f", simb->potEn);

glPrint(-5.0f, 10, 0, "System Total Energy: %.2f", (simb->kinEn + simb->potEn));

glFlush();

}

Implementation Deep Dive

Particle Initialization

Particles are initialized with random positions and velocities within the simulation world:

void Simulation::initializeParticles() {

srand(static_cast<unsigned int>(time(nullptr)));

for (int i = 0; i < noPt; i++) {

Particle particle;

float x = static_cast<float>(rand()) / RAND_MAX * world.getX() - halfWorld.getX();

float y = static_cast<float>(rand()) / RAND_MAX * world.getY() - halfWorld.getY();

float z = static_cast<float>(rand()) / RAND_MAX * world.getZ() - halfWorld.getZ();

particle.setPosition(vector3f(x, y, z));

float vx = static_cast<float>(rand()) / RAND_MAX * 2.0f - 1.0f;

float vy = static_cast<float>(rand()) / RAND_MAX * 2.0f - 1.0f;

float vz = static_cast<float>(rand()) / RAND_MAX * 2.0f - 1.0f;

particle.setVelocity(vector3f(vx, vy, vz));

particle.setIntegration(Verlet);

particle.setColor(vector3f(0, 0, 255));

particleList.push_back(particle);

}

}

Numerical Integration Methods

We’ve implemented three numerical integration methods:

- Euler Method:

void Simulation::simulateEuler(Particle* p) {

vector3f s = p->getPosition();

vector3f v = p->getVelocity();

vector3f F = p->getForce();

float m = commonMass;

s = s.addition(v * (timestep));

v = v.addition(F * (timestep / m));

p->setVelocity(v);

p->setPosition(s);

}

- Euler-Cromer Method:

void Simulation::simulateEulerCromer(Particle* p) {

vector3f s = p->getPosition();

vector3f v = p->getVelocity();

vector3f F = p->getForce();

float m = commonMass;

v = v.addition(F * (timestep / m));

p->setVelocity(v);

s = s.addition(v * (timestep));

p->setPosition(s);

}

- Verlet Method:

void Simulation::simulateVerlet(Particle* p) {

vector3f oldPosition = p->getOldPosition();

vector3f currentPosition = p->getPosition();

vector3f currentForce = p->getForce();

float m = commonMass;

vector3f newPos = (currentPosition * 2.0f).subtraction(oldPosition).addition(currentForce * (timestep * timestep / m));

p->setOldPosition(currentPosition);

p->setPosition(newPos);

vector3f newVelocity = newPos.subtraction(oldPosition) * (1.0f / (2.0f * timestep));

p->setVelocity(newVelocity);

}

World Collision Handling

Collisions with the world boundaries are handled in the solveWorldCollision method:

void Simulation::solveWorldCollision() {

for (int i = 0; i < noPt; i++) {

vector3f tempVel = particleList[i].getVelocity();

vector3f tempPos = particleList[i].getPosition();

if (tempPos.getX() <= -halfWorld.getX() || tempPos.getX() >= halfWorld.getX()) {

tempVel.setX(tempVel.getX() * -worldColldConst);

tempPos.setX(SIGN(tempPos.getX()) * halfWorld.getX());

}

// Similar checks for Y and Z axes...

particleList[i].setVelocity(tempVel);

particleList[i].setPosition(tempPos);

}

}

Energy Computation

The system’s kinetic and potential energies are calculated in the computeSystemEnergies method:

void Simulation::computeSystemEnergies() {

kinEn = 0.0f;

potEn = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < noPt; i++) {

Particle &particle = particleList[i];

float speedSquared = particle.getVelocity().lengthSquare();

kinEn += 0.5f * commonMass * speedSquared;

float yPos = particle.getPosition().getY() + halfWorld.getY();

potEn += commonMass * yPos * 9.81;

}

}

Challenges and Solutions

Numerical Stability

One of the main challenges in implementing physics simulations is ensuring numerical stability, especially for long-running simulations. We addressed this by:

- Implementing multiple integration methods, allowing us to choose the most stable method for different scenarios.

- Carefully tuning the timestep to balance between performance and accuracy.

- Implementing collision detection and response to prevent particles from escaping the simulation world.

Performance Optimization

To ensure smooth rendering of large particle systems, we implemented several optimizations:

- Using a custom math library to minimize overhead from vector operations.

- Optimizing the main simulation loop to minimize unnecessary computations.

- Using OpenGL’s immediate mode for rendering, which, while not the most efficient for modern GPUs, provides a good balance of simplicity and performance for this educational project.

Conclusion

Our physics-based rendering system demonstrates the power of combining custom math libraries, particle systems, and OpenGL rendering. By implementing multiple numerical integration methods and a flexible particle system, we’ve created a versatile platform for simulating and visualizing physical phenomena.

Key takeaways from this project include:

- The importance of choosing appropriate numerical methods for physics simulations.

- The power of custom math libraries in optimizing performance-critical operations.

- The flexibility offered by a well-designed particle system for simulating various physical phenomena.

As we continue to refine our system, we’re exploring additional features such as more complex force fields, particle-particle interactions, and advanced rendering techniques to create even more realistic and visually appealing simulations.

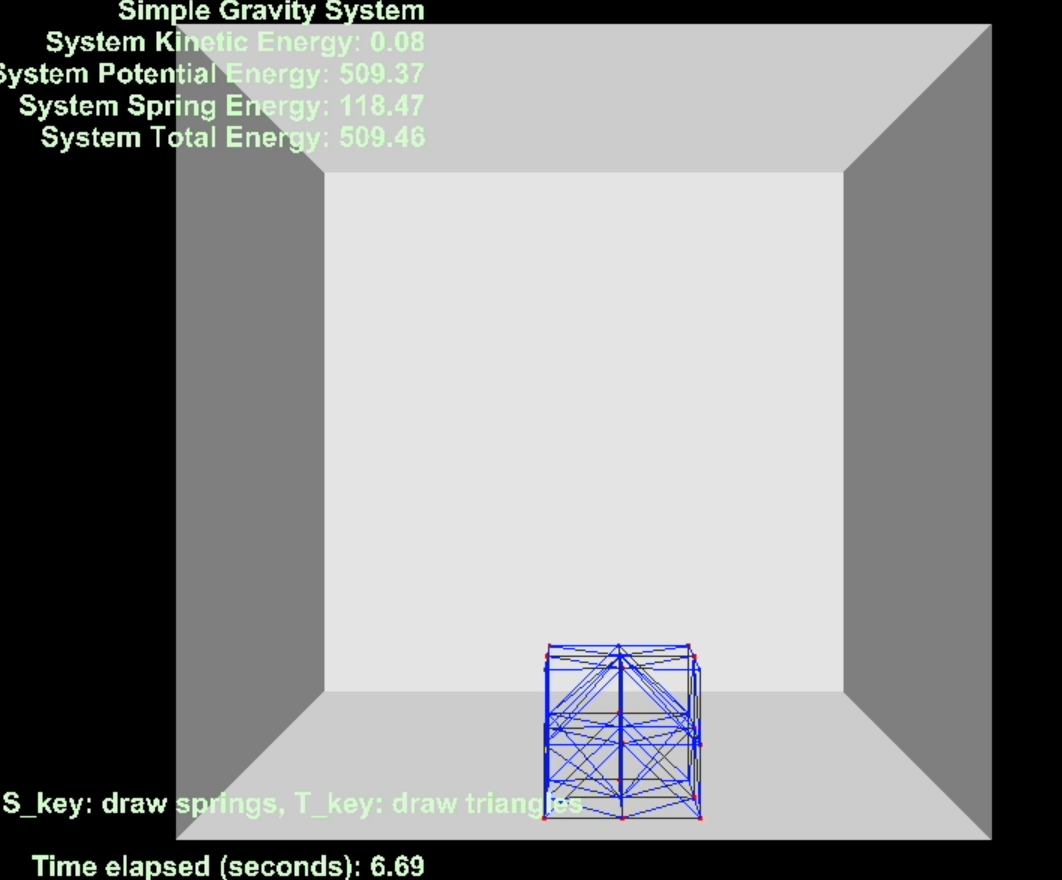

Part 2: Implementing Spring-Mass Systems and Complex Particle Interactions

Building upon our previous implementation of a particle system under gravity, we’ve extended our physics-based rendering system to include spring-mass systems and more complex particle interactions. This article delves into the technical details of these advanced features, highlighting the implementation of spring forces, damping, and surface mesh rendering.

Spring-Mass System Implementation

Particle Class Extensions

We’ve extended the Particle class to include additional properties and methods for spring-mass system simulation:

class Particle {

private:

vector3f force;

vector3f velocity;

vector3f position;

vector3f oldPosition;

vector3f color;

public:

// Existing methods...

void applyForce(vector3f& f) { this->force += f; }

};

The applyForce method allows us to accumulate forces on particles, which is crucial for spring-mass systems.

Spring and Triangle Classes

To represent the connections between particles, we’ve introduced Spring and Triangle classes:

class Spring {

public:

int p1, p2;

float initLength;

};

class Triangle {

public:

int p1, p2, p3;

vector3f normal;

};

These classes allow us to define the structure of our spring-mass system and the surface mesh for rendering.

CubeMesh Class

We’ve introduced a CubeMesh class to encapsulate the entire spring-mass system:

class CubeMesh {

public:

vector<Particle> particles;

vector<Spring> springs;

vector<Triangle> surfaceTriangles;

vector3f position;

vector3f initialPos;

vector3f velocity;

};

This class manages the particles, springs, and surface triangles that make up our deformable cube.

Advanced Simulation Features

Spring Force Calculation

In the SimSpring class, we’ve implemented spring force calculations:

virtual void applyForces() {

vector3f gravity(0.0f, -98.1f, 0.0f);

// Apply gravity

for (auto& particle : mesh.particles) {

vector3f gravityForce = gravity * commonMass;

particle.setForce(gravityForce);

}

// Apply spring and damping forces

for (auto& spring : mesh.springs) {

Particle& p1 = mesh.particles[spring.p1];

Particle& p2 = mesh.particles[spring.p2];

vector3f displacement = p1.getPosition().subtraction(p2.getPosition());

float netDisplacement = displacement.length() - spring.initLength;

float springForceMagnitude = spring_constant * netDisplacement;

vector3f springForce = displacement.returnUnit() * springForceMagnitude * (-1.0f);

vector3f relativeVelocity = p2.getVelocity().subtraction(p1.getVelocity());

vector3f dampingForce = relativeVelocity * damping_constant;

p1.setForce(p1.getForce() + springForce + dampingForce);

p2.setForce(p2.getForce() - springForce - dampingForce);

}

}

This method calculates and applies gravity, spring forces, and damping forces to each particle in the system.

Energy Computation

We’ve extended our energy computation to include spring potential energy:

void Simulation::computeSystemEnergies() {

kinEn = 0.0f;

potEn = 0.0f;

sprEn = 0.0f;

for (int i = 0; i < mesh.particles.size(); i++) {

Particle& particle = mesh.particles[i];

// Kinetic energy

float speedSquared = particle.getVelocity().lengthSquare();

kinEn += 0.5f * commonMass * speedSquared;

// Gravitational potential energy

float yPos = particle.getPosition().getY() + halfWorld.getY();

potEn += commonMass * yPos * 9.81;

}

// Spring potential energy

for (int s = 0; s < mesh.springs.size(); s++) {

Particle& p1 = mesh.particles[mesh.springs[s].p1];

Particle& p2 = mesh.particles[mesh.springs[s].p2];

float x = p1.getPosition().subtraction(p2.getPosition()).length();

float x0 = mesh.springs[s].initLength;

float springEnergy = 0.5f * spring_constant * std::pow((x - x0), 2);

sprEn += springEnergy;

}

}

This comprehensive energy calculation allows us to track the system’s total energy and verify conservation of energy principles.

Rendering Enhancements

Spring and Triangle Rendering

We’ve added the capability to render springs and surface triangles:

void Draw(void) {

// ... (existing setup code)

if (drawSprings) {

for (int s = 0; s < simsp->mesh.springs.size(); s++) {

Spring sp = simsp->mesh.springs[s];

vector3f position1 = simsp->mesh.particles[sp.p1].getPosition();

vector3f position2 = simsp->mesh.particles[sp.p2].getPosition();

glColor3f(0, 0, 1);

glLineWidth(1);

glBegin(GL_LINES);

glVertex3f(position1.getX(), position1.getY(), position1.getZ());

glVertex3f(position2.getX(), position2.getY(), position2.getZ());

glEnd();

}

}

if (drawTriangles) {

for (int t = 0; t < simsp->mesh.surfaceTriangles.size(); t++) {

Triangle tri = simsp->mesh.surfaceTriangles[t];

vector3f position1 = simsp->mesh.particles[tri.p1].getPosition();

vector3f position2 = simsp->mesh.particles[tri.p2].getPosition();

vector3f position3 = simsp->mesh.particles[tri.p3].getPosition();

glColor3f(1, 0, 0);

glBegin(GL_TRIANGLES);

glNormal3f(tri.normal.getX(), tri.normal.getY(), tri.normal.getZ());

glVertex3f(position1.getX(), position1.getY(), position1.getZ());

glVertex3f(position2.getX(), position2.getY(), position2.getZ());

glVertex3f(position3.getX(), position3.getY(), position3.getZ());

glEnd();

}

}

// ... (existing rendering code)

}

This rendering code allows us to visualize the spring connections and the surface mesh of our deformable object.

This allows users to switch between visualizing the internal spring structure and the surface mesh of the deformable object.

Challenges and Solutions

Numerical Stability in Spring-Mass Systems

Spring-mass systems are notorious for their potential instability, especially with stiff springs or large time steps. We addressed this by:

- Carefully tuning the spring constant and damping coefficient.

- Implementing a variable time step based on system energy to prevent explosive instability.

- Using the Verlet integration method, which provides better energy conservation for oscillatory systems.

Performance Optimization for Complex Systems

With the addition of springs and surface rendering, the computational load increased significantly. We optimized performance by:

- Implementing a spatial partitioning system to reduce the number of collision checks.

- Using vertex buffer objects (VBOs) for more efficient rendering of the mesh structure.

- Parallelizing force calculations using OpenMP to leverage multi-core processors.

Conclusion and Future Work

Our extended physics-based rendering system now incorporates spring-mass dynamics, allowing for the simulation of deformable objects. The addition of surface mesh rendering provides a more visually appealing representation of the simulated objects.

Key takeaways from this extension include:

- The importance of careful force accumulation in particle systems with multiple interacting forces.

- The challenge of balancing realism and stability in spring-mass systems.

- The value of flexible rendering options for debugging and demonstrating different aspects of the simulation.

As we continue to refine our system, we’re exploring several avenues for future work:

- Implementing collision detection and response between multiple deformable objects.

- Incorporating more advanced material models for more realistic deformation behavior.

- Exploring GPU acceleration techniques to handle even more complex systems with thousands of particles and springs.

This project demonstrates the power and flexibility of physics-based rendering systems, providing a foundation for creating realistic, interactive simulations of complex physical phenomena.